Humanity has had rather more intelligence than wisdom, and especially so in the last two centuries. Nowhere is this more crystal-clear than when we talk about water.

Civilizations have developed powerful and far-reaching human societies over millennia, even in arid areas, by carefully stewarding water resources. The ancient Chinese, the Nabataeans of the ancient city of Petra, and the Egyptian, Ottoman and Roman empires were driven partly by their development of innovations for water storage, distribution, and transport of grey water and sewage.

Even large-scale distribution of water from unpredictable rivers sometimes enabled agriculture to flourish, largely because these civilizations were fundamentally limited – in terms of their economies, populations, movements, and quality of life – by water. Even so, the seasonal migration of people was, and still is, a common practice in response to seasonal variation in water, grazing for animals, and climate.

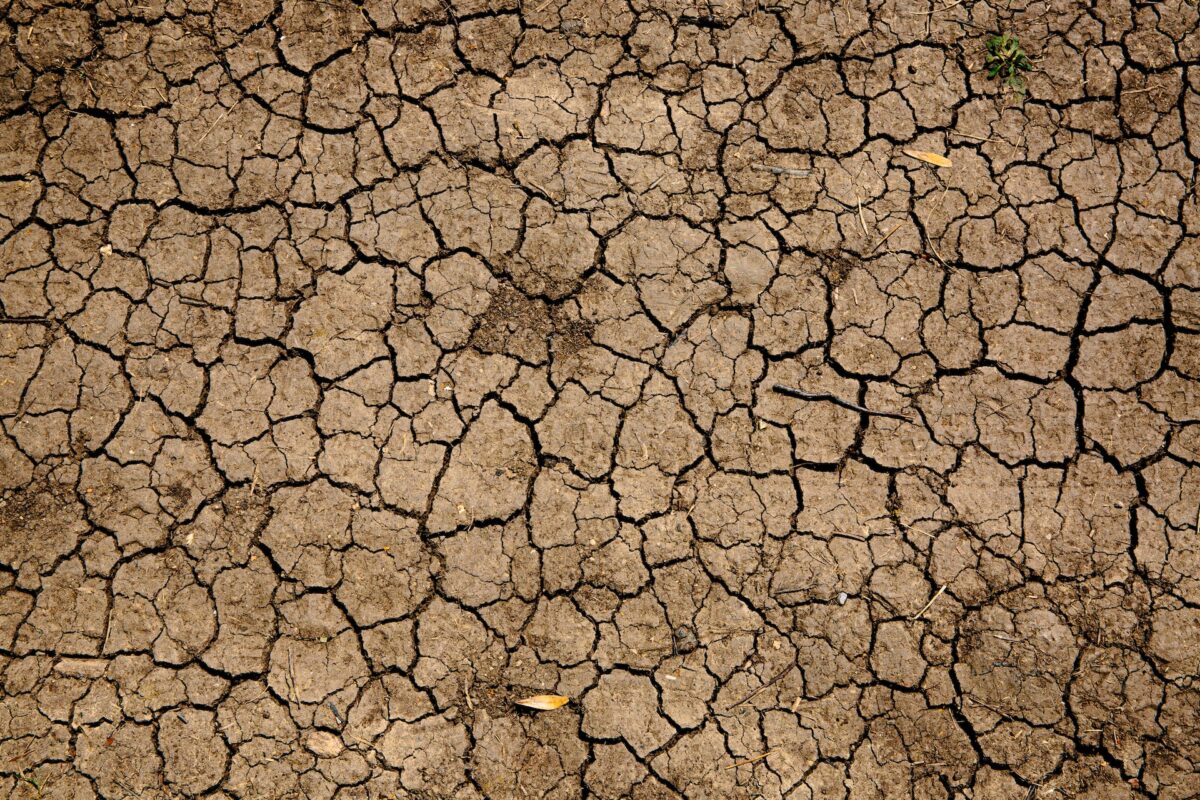

Groundwater wells around the world supply water to billions of people. And groundwater makes up just over 30% of all freshwater. But when population and economic growth outstrip water tables, these wells can quite quickly run dry as the water table drops. Many of us in arid lands have experienced public and private overconsumption of what are often called ‘fossil aquifers‘ – large underground water reserves that formed under past climatic and geological conditions.

Fossil aquifers often underlie current-day arid and semi-arid environments, and are thus a tempting source of groundwater in otherwise water scarce regions. But because they are not being recharged by rainwater, or at least not nearly fast enough, their exploitation is unwise. Small-scale use for subsistence is often possible, but can easily lead to excessive abstraction.

How serious is our current groundwater situation on Earth? Well, pretty serious. Globally, we are heading into a perfect storm, and need to take rapid action to avert it.

Scott Jasechko and Debra Perrone, two analysts at the University of California at Santa Barbara, analyzed records on the construction of roughly 39 million groundwater wells in 40 countries worldwide. Of these, as many as 1 in 5 were shallow: no more than 5 meters deeper than the water table. Their 2021 paper in Science showed that not only are millions of wells at risk of running dry with declining water tables, but newly constructed wells are not being dug deeper, and are thus at least as likely as older wells to run dry in many areas. This poses real water security risks to millions of farmers, landowners and urban dwellers.

It is often said that many of the world’s future conflicts will be about water. While people in arid countries, and their governments, seldom take water for granted, much water consumption in the wealthy world has mushroomed with piped irrigation and water supply to households, companies and farms. And this is not unique to temperate ecosystems like many in northwestern Europe or North America. The United Arab Emirates (UAE), Botswana, Israel, Australia, Egypt and South Africa are six of the world’s top 15 ‘per-capital water footprint’ countries.

And apart from the matter of quantity of water and basic access, there is water quality. Deep fossil aquifers, apart from being hard and expensive to access by deep wells, may sometimes have surprisingly poor water quality. This could be for several reasons, including the basic principle that the water in shallower wells originates from the immediate area, whereas that in deeper wells can draw from a large. While shallow wells can be easily contaminated by local runoff, including urban and agricultural pollutants, these contaminants can also reach deep aquifers through porous rock.

As humanity has finally acknowledged that its suite of toxic chemicals for modern life, from PCBs, dioxins and microplastics to birth-control hormones and herbicides, do not disappear when flushed down toilets or applied to crops, we now realize that many of these chemicals are increasingly common in groundwater, in oceans, on mountaintops and even in sea fog.

Living and working on environmental protection strategies for 34 years in arid Namibia and South Africa, I kept water at the forefront of my thinking, planning and teaching – from politicians and my university students to my own daughters. Namibia, the driest country south of the Sahara Desert, has no perennial rivers and few major aquifers within its borders. The Kunene and Okavango Rivers on its northern border are shared with (and arise in) Angola and Zambia, and the Orange / Gariep River on its southern border arises in Lesotho and South Africa. Namibia is therefore extremely cautious about its national water security, and has co-developed regional river basin commissions with its neighbors, sometimes having to thwart its own development plans.

Water is life – particularly in the driest countries. The economies of the UAE, Botswana, Israel, Australia, Egypt and South Africa have much to learn from their past and current mistakes – and much to profit from this effort.

Image credit: Mike Erskine